Tax Savvy Produces Conservation and a Family Legacy

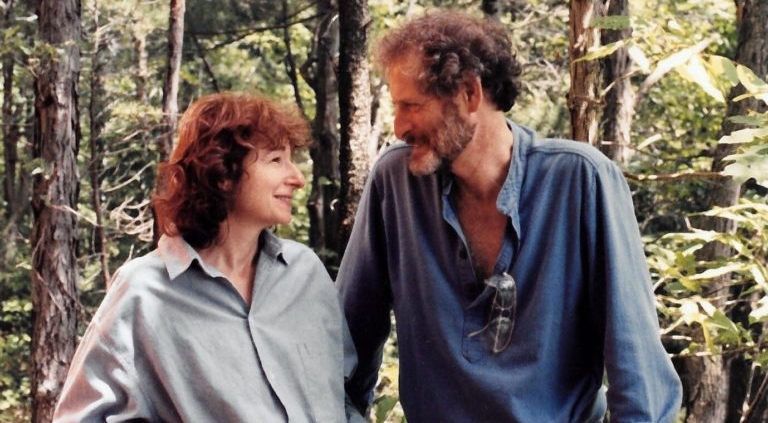

In 1969, an American couple canoed around the Thousand Islands of Ontario. Ada and Joel Farber had both camped in the Adirondack and Pocono Mountains of New York State when they were children. The Canadian Thousand Islands region had a similar feel, inviting and less populated than New York, so they looked for property to purchase. The Farbers found five parcels along a stretch of the Gananoque River, in an area known as Lost Bay. The land cast a spell over them. One parcel had high cliffs rising from the water which reminded Ada and Joel of the rocky ledge in Heinrich Heine’s famous poem about an enchanting mermaid seductress, so they named it Loralei.

Ted Kaiser

Ted Kaiser Lost Bay Beaver Pond, Ted Kaiser

Almost fifty years later, the Farbers were trying to figure out how to keep the most cherished of the five parcels in the family. “We wanted to do the right thing for our kids and the land,” recalls Joel. “Our son, Jonathan, had grown up on the land and loved it. He had a particular interest in the large piece we called Wolfgang, which is across the river from our cabin. When we were new to the area, we thought we heard wolves across the river, so we called it Wolfgang as we’re Mozart lovers. Our other son, however had no interest in the properties.” A major obstacle to doing the right thing was the significant Canadian capital gains tax Joel and Ada (or their estate) would owe if they gifted or bequeathed property to their sons.

Ted Kaiser

Ted Kaiser Snake Island in Lost Bay Lake, Ted Kaiser

Cameron Smith, a local conservation leader from the Kingston Field Naturalists Club, suggested that Ada and Joel reach out to Sandra Tassel of American Friends of Canadian Conservation (American Friends) about how to achieve their two goals. The Farbers had many conversations with Sandy over the course of several years. After she fully understood the family’s needs and finances, Sandy suggested they donate Loralei, together with a conservation easement on Wolfgang, to a Canadian land trust through the Canadian Ecological Gifts Program (EGP), instead of seeking a U.S. tax deduction. The Canadian tax credit for those gifts, available through EGP, would offset the Canadian capital gains tax on gifting the family cabin and Wolfgang to Jonathan.

Per Verdonk, Flickr

Per Verdonk, Flickr White Admiral by Per Verdonk, Flickr

Sandy recalls, “Cameron referred the Farbers to me because they are U.S. taxpayers. Everyone assumed that a U.S. tax deduction would convince Joel and Ada to donate and therefore they should gift their property to American Friends. But our work at the intersection of the U.S. and Canadian tax systems has taught us to look at all the possibilities. This was a situation where our knowledge was more important to successful conservation than accepting the land donation.”

After conferring with an accountant with crossborder expertise, Joel and Ada implemented Sandy’s suggestion. They donated the easement on Wolfgang and ownership of Loralei to Ontario Nature to expand the 588-acre Lost Bay Nature Reserve. The Canadian tax credit completely offset the capital gains taxes on both the transfer to Jon and on the sale of two building lots, which generated money so Joel and Ada could provide financial support to their other son.

Joel said, “It was very important to us that Wolfgang remain undeveloped,” he explained. “The conservation easement prevents any building or any permanent changes to Wolfgang, but Jon will own the property and the parcel with the cabin on the other side of the river. There’s got to be some place where humans don’t have the upper hand.”

Cameron Smith put the Farbers’ donations in the broader context. “The Gananoque River and Lost Bay are within the Frontenac Arch Biosphere Reserve — one of only eighteen in Canada. The Arch connects the Canadian Shield to the Appalachians, providing the most important north/south ecological pathway in eastern North America.” The easement on Wolfgang completed the protection of an entire side of Lost Bay, opposite an increasing number of waterfront cottages. Property values have quadrupled since the start of the Covid pandemic, making the timing of the Farbers’ donations fortuitous.

Dylan Martin, Flickr

Dylan Martin, Flickr Yellow Spotted Salamander, cropped by Dylan Martin, Flickr

Tanya Pulfer, former Project Manager with Ontario Nature, says Lost Bay is a highly-prized recreation area, and home to a number of species at risk. “Sandy figured out the conservation and crossborder tax structure. The family was really interested in seeing the land protected, yet they also had to address monetary and estate-planning concerns. Not only is their son interested in maintaining an interest in the land, but their granddaughter is also, so a family legacy is going forward.”

Without the solution tailored to the Farbers’ objectives, Joel and Ada would have sold the building lots, paid the tax on the sales, kept the other parcels and a substantial capital gains taxes would have been due when they passed away. The conservation opportunity would have been lost. That is why AF’s “technical assistance” plays such a valuable, although often invisible, role in Canadian landscapes where U.S. taxpayers own ecologically significant properties.

This cross-border conservation gift and easement mean so much to the landowners and their heirs, and also to Ontario Nature, The Lost Bay Reserve, and the larger Frontenac Arch. The migrating loons and other wildlife that cross from the Appalachians to the Canadian Shield can rest easy with their young, as this area is now protected forever.

— Sheila Harrington

Sheila is a Director of the Lasqueti Island Nature Conservancy in British Columbia (BC) and the former Executive Director, Land Trust Alliance of BC